People In This Italian City Still Live In 9,000-Year-Old Cave Homes (And You Can Too)

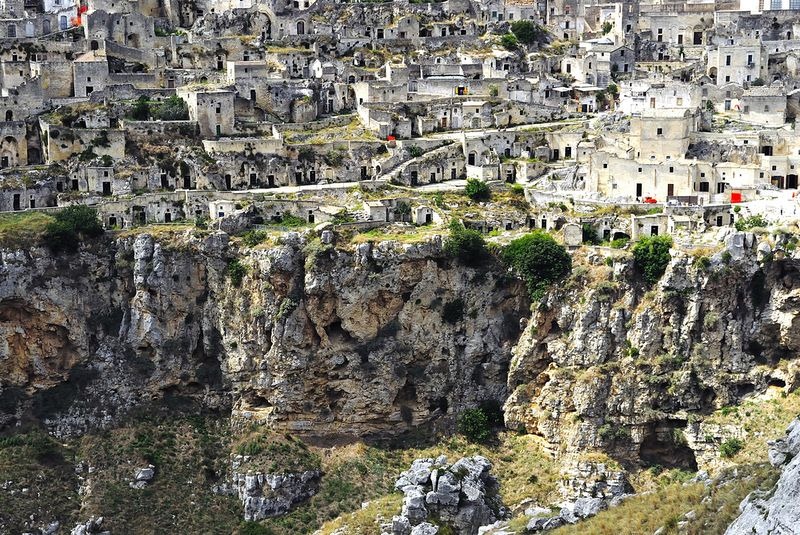

“Sassi” cave dwellings cascade in gravity-defying fashion in Matera.

Time should tick slowly in a city like Matera. Claimed as the third-oldest continually inhabited settlement in the world (after Aleppo and Jericho), the southern Italian city has been home to someone for at least 9000 years. But by any standards, the last 70 years in Matera have been a whirlwind.

In 1950, the impoverished city was declared the “shame of Italy” by the country’s prime minister of the day, a pronouncement that culminated in the eviction of 15,000 residents living in the caves that punctured a deep ravine running through the city.

Today, Matera is a place reborn. Its caves are filled with restaurants, bars, hotels and souvenir stores, and the city is a Hollywood darling. In 2019, it will take centre stage as Europe’s Capital of Culture.

Filmmakers have adopted Matera as the body double of choice for Biblical-era cities.

What stands Matera apart for visitors are the cave regions, or sassi (meaning ‘stone’ in Italian), that line the ravine – up higher, on the plateau, the modern city barely gets a passing glimpse. Thousands of caves perforate the hard stone, climbing up the slopes of the ravine so that one cave’s ceiling is often the next cave’s floor.

Stone-brick facades provide a visual semblance of civilisation, but as you wander the narrow lanes that run higgledy-piggledy courses through the caves, you are inevitably walking over the roofs of the homes. Chimneys erupt from the cobblestones, and it’s a stroll through what half-resembles a raw, landlocked Santorini.

More than 2000 people live among the caves, typically renting them from the government, which owns 70 per cent of the sassi.

The best walks here are the aimless ones – up alleys, down lanes – threading among the homes and Matera’s 155 cave churches, which were mostly built in the 11th and 12th centuries and now deconsecrated.

At times it seems there are almost as many lookouts as churches in the sassi. Come to any edge and there’s inevitably a “belvedere” peering out over the deep ravine and the sassi. View it like this, as a puzzle of stone houses on stone slopes, and it’s easy to see why filmmakers have adopted Matera as the body double of choice for Biblical-era cities.

In the 1960s, Pier Paolo Pasolini shot The Gospel According to St Matthew in the then-forlorn city; in 2004, it was Mel Gibson with The Passion of the Christ. In 2015, the new Ben Hur rolled through Matera, and Gibson will be back in 2017 filming a sequel to The Passion.

With its limestone cave dwellings dug in the hillside, this is one of the Italian cities that time forgot.

It’s a long way from the time when Matera’s sole appearance in popular culture was in Carlo Levi’s 1945 book about his exile in southern Italy, Christ Stopped at Eboli. In it, Levi likened the sassi to a “schoolboy’s idea of Dante’s Inferno”.

If there’s more fame than shame now in Matera, it’s reflected in the sassi, where more than 2000 people live among the caves again, typically renting them from the government, which owns 70 per cent of the sassi.

At the top of the sassi is Matera’s historic centre, where in the Renaissance, wealthier residents built their mansions and palaces. Known locally as Il Piano because it’s flat, the historic centre is lined with boutique stores and crowned by Matera’s cathedral.

Matera’s Sassi limestone cave dwellings in southern Italy.

The cathedral recently reopened after 12 years closed for restoration, with its sober Renaissance exterior belying a baroque interior that seems excessively florid after the muted tones of the sassi.

Among it all there remain glimpses of Matera’s ghosts. The sassi are broken into two sections, Sasso Barisano and Sasso Caveoso, with most of the restoration taking place in Barisano, leaving the caves of Caveoso sitting as empty eyed as a skull.

Near the cathedral, Casa Noha tells the story of Matera in an excellent 20-minute video, while beneath the prominent Madonna de Idris rock outcrop, Casa Grotta provides a look at a cave furnished as it was in the days of shame.

Back then, up to 11 people lived in a cave, with their animals also inside to provide warmth. There were no toilet facilities, and the city had no water source, so an ingenious system of rainwater channels and cisterns was excavated beneath homes – it was these channels and cisterns, not the city’s history or architecture, that earned Matera a place on Unesco’s World Heritage list in 1993.

Beds sat high off the floor to escape the humidity from the cisterns, and young children often slept in drawers pulled open for the night. Child mortality rates exceeded 50 per cent.

Step back out of Casa Grotta, into modern Matera, and such history feels impossible in this sassi city that’s now very much a sassy city.